Cooking Shrimp Jambalaya with Mme. Bégué

Many years ago, I ran across the Antique American Cookbooks collection printed by Oxmoor House in 1984 when I discovered one of the eight volumes in a resale shop. Since then, I grab one up every chance I get – they aren’t easy to find.

One of my favorites is Mme. Begué and Her recipes: Old Creole Cookery. You can read a copy on the Library of Congress website.

That’s pretty cool, right?

Madame Bégué

While Mme. Bégué was well known for her Creole cooking, she was no Creole.

Elizabeth Kettenring was a Bavarian chef who moved to New Orleans in 1853 to visit her brother. While there, she met and later married Louis Dutreuil, a friend of her brother’s. Together, they opened Dutrey’s – restaurant serving German food to a hungry crowd who worked at the French Market. Dutrey’s was named so because it was easier for folks to pronounce than Dutreuil. When Dutreuil died in 1875, Elizabeth managed the restaurant on her own.

In 1880, she married Frenchman Hypolite Bégué. Legend has it, he worked as a bartender in Dutrey’s because he loved the food so much. He did, however, take credit for convincing Elizabeth to add French food to the restaurant’s menu. WIth a new sirname came a new restaurant name. By 1884, people were flocking to Bégués for the “one meal a day”

Second Breakfast

Mme. Bégué served only one meal a day – a second breakfast at 11:00 AM. This was, indeed, on purpose as it provided a meal for those who had been working in the market and on the docks since dawn.

Brunch was born! Thanks to Mme. Bégué.

Each meal was six courses: heavy soup, shrimp or crawfish, fish, quail in wine sauce, fresh salad, and dessert was typical. Shrimp jambalaya was undoubtedly included in the second course.

After Elizabeth’s death in 1906, the restaurant was closed for a bit. Then reopened when Hypolite married a former employee. The restaurant changed hands a few times, but today, dine in the same rooms where brunch was invented – at Tujague’s

The Cookbook

Bégué’s was so popular among both residents and visitors, that the Southern Pacific RailwaySouthern Pacific Railway. saw an opportunity. Recipes from the restaurant were compiled and, in 1900, Mme. Begué and Her recipes was published as an attempt to entice those who read it to hop the train to New Orleans.

Southern Pacific Railway funded the printing and distribution of the cookbook. It was also sold at the end of the meal at Bégué’s.

On a side note – in my day job, I’m a professor of tourism and culinary tourism is kind of my thing. This … by all intents and purposes … is the earliest form of purposeful culinary tourism. Imagine, in the days before marketing destinations was commonplace, a railway company saw an opportunity to get people to purchase train tickets to a restaurant! Let alone New Orleans.

But I digress. Sort of.

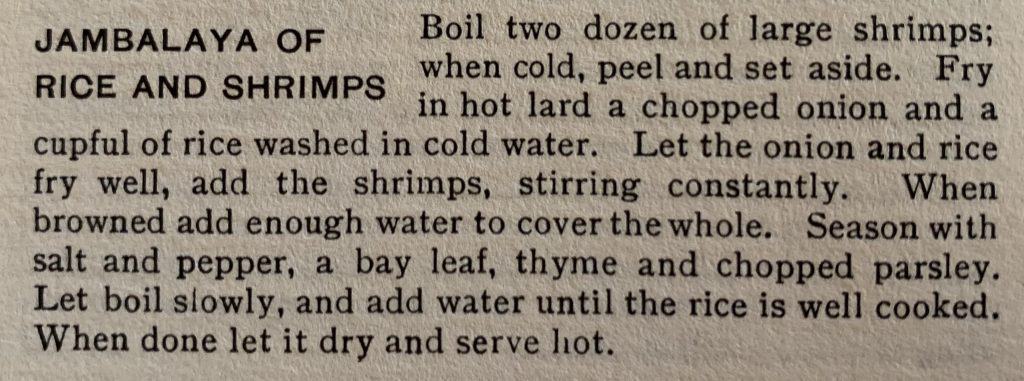

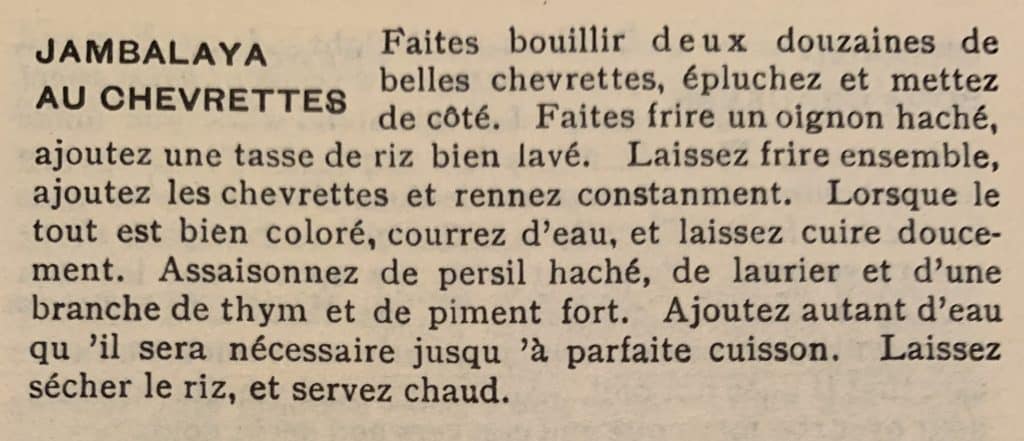

The cookbook includes a variety of Creole dishes in English and French. Some are familiar like Jambalaya of Rice and Shrimps (aka Shrimp Jambalaya) while others are less so. Oysters, shrimp, crawfish, fish, and eggs are frequent ingredients. Snails and turtles make an appearance, as do veal and lamb.

Shrimp Jambalaya

My family loves shrimp jambalaya and I make it a little different each time. I don’t think I’ve ever made it “correctly”, however. So, I’ve rearranged Mme. Bégué’s Jambalaya of Rice and Shrimps for a family of four using modern kitchen appliances – namely a gas stove!

But, just because I love old recipes – below is the original in English and French. What is noticeably missing in this Creole jambalaya is tomatoes.

Creole is a term describing with descendants of the early French and Spanish settlers in New Orleans and the immediate region. More specifically, French Creole described someone of European ancestry while Louisiana Creole described someone of mixed racial ancestry that included African.

Creole cuisine is a mixture of all these cultures plus a few more including Italian and German. In New Orleans history, Creole cuisine was more aristocratic than its country Cajun counterpart.

Tomatoes are common in Creole cooking, largely due to the access our early “high brow” city dwellers had to tomatoes from Sicily – something Cajun folks didn’t have. This tidbit makes the omission of tomatoes from Mme. Bégué’s recipe all the more curious.

Another interesting ingredient is lard over the more common butter. The French Holy Trinity of onions, celery, and bell pepper is also missing. Both butter and the Holy Trinity are Creole cooking staples thanks to French influence.

So now my brain hurts.

Here’s my theory. Elizabeth’s German roots influenced her Creole cooking and lard replaced butter while tomatoes were left out. Another thought points to her early clientele of not aristocratic city folk but humble dock workers.

I can say that my husband – who despises tomatoes – ate seconds! He now loves Mme. Bégué. I’m okay with that!